Big Five Model of Personality

Acronym

FFM, OCEAN

Alternate name(s)

Five Factor Model of Personality, OCEAN Model of Personality

Main dependent construct(s)/factor(s)

Psychological distress, social activity, creativity, cooperativeness, self-discipline

Main independent construct(s)/factor(s)

Cultural factors, biological factors

Concise description of theory

The Big Five model of personality, known as the Five-Factor Model (FFM), is a widely recognized and extensively researched psychological framework aimed at capturing fundamental dimensions of human personality. This theory’s origins can be traced back to groundbreaking work by pioneering researchers like Ernest Tupes, Raymond Christal (1958), and Lewis Goldberg (1982) during the mid-20th century. During the 1980s and 1990s Paul T. Costa and Robert R. McCrae further developed the comprehensive Big Five model. This model identified five broad dimensions of personality namely Neuroticism, Extraversion, Openness to Experience, Agreeableness, and Conscientiousness. McCrae and Costa developed the NEO-PI to measure these personality traits. They have specified six specific facets that comprise each of the big five factors. The first factor Neuroticism represents the individual’s tendency to experience psychological distress (Costa & McCrae, 1992a). The six underlying facets of Neuroticism are anxiety, angry hostility, depression, self-consciousness, impulsiveness, and vulnerability. Extraversion is the factor explaining the individual's tendency to engage in social activity (Costa & McCrae, 1992b). The underlying facets of extraversion are warmth, gregariousness, assertiveness, activity, excitement-seeking, and positive emotions. The next factor, Openness to experience, explains an individual’s tendency to be open to experience, intellect, and culture (Costa & McCrae, 1992b). Underlying facets of Openness to experience are fantasy, aesthetics, feelings, actions, ideas, and values. The Agreeableness factor explains an individual’s friendly compliance and socialization (Costa & McCrae, 1992b). Trust, straightforwardness, altruism, compliance, modesty, and tender mindedness are the facets underlying Agreeableness. The last factor Conscientiousness explains an individual’s tendency to be scrupulous, well-organized, and diligent (Costa & McCrae, 1992a). The facets underlying Conscientiousness are competence, order, dutifulness, achievement striving, self-discipline, and deliberation.

Over time, the Big Five model has gained widespread acceptance due to its robustness and cross-cultural applicability. Rigorous research, including longitudinal studies and investigations across diverse societies, has further validated its stability and significance. Today, the Big Five model remains a prominent theoretical framework in personality psychology, offering a comprehensive understanding of individual differences in personality traits. Its applications encompass diverse domains, including psychological research, clinical practice, organizational behavior, and popular personality assessments.

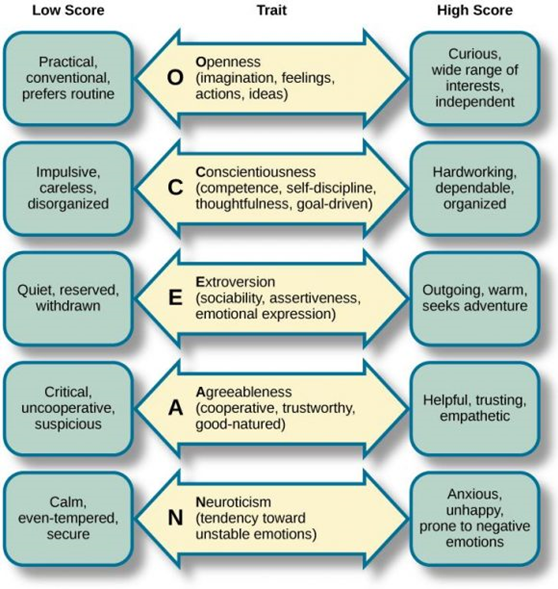

Diagram/schematic of theory

- Figure 1: Big Five Factors of Personality

.

Originating author(s)

- Ernest Tupes and Raymond Christal (1958)

- Lewis Goldberg (1982)

- Paul T. Costa and Robert R. McCrae (1992)

Seminal article(s)

1. Goldberg, L. R. (1990). An alternative" description of personality": the big-five factor structure. Journal of personality and social psychology, 59(6), 1216.

2. Costa, P. T., & McCrae, R. R. (1992). Normal personality assessment in clinical practice: The NEO Personality Inventory. Psychological assessment, 4(1), 5.

3. McCrae, R. R., & Costa Jr, P. T. (1997). Personality trait structure as a human universal. American psychologist, 52 (5), 509.

4. John, O. P., & Srivastava, S. (1999). The Big-Five trait taxonomy: History, measurement, and theoretical perspectives.

Level of analysis

Individual

IS articles that use the theory

- Devaraj, S., Easley, R. F., & Crant, J. M. (2008). Research note—how does personality matter? Relating the five-factor model to technology acceptance and use. Information systems research, 19(1), 93-105.

- Everton, W. J., Mastrangelo, P. M., & Jolton, J. A. (2005). Personality correlates of employees' personal use of work computers. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 8(2), 143-153.

- Junglas, I. A., Johnson, N. A., & Spitzmüller, C. (2008). Personality traits and concern for privacy: an empirical study in the context of location-based services. European Journal of Information Systems, 17, 387-402.

- Junglas, I., & Spitzmuller, C. (2006, June). Personality traits and privacy perceptions: an empirical study in the context of location-based services. In 2006 International Conference on Mobile Business (pp. 36-36). IEEE.

- Khan, M., Iahad, N. A., & Mikson, S. (2014). Exploring the influence of big five personality traits towards computer based learning (CBL) adoption. Journal of Information Systems Research and Innovation, 8, 1-8.

- Korukonda, A. R. (2005). Personality, individual characteristics, and predisposition to technophobia: some answers, questions, and points to ponder about. Information Sciences, 170(2-4), 309-328.

- Korukonda, A. R. (2007). Differences that do matter: A dialectic analysis of individual characteristics and personality dimensions contributing to computer anxiety. Computers in human behavior, 23(4), 1921–1942.

- Krishnan, S., Lim, V. K., & Teo, T. S. (2010). How does personality matter? Investigating the impact of big-five personality traits on cyberloafing.

- Marcus, B., Machilek, F., & Schütz, A. (2006). Personality in cyberspace: personal Web sites as media for personality expressions and impressions. Journal of personality and social psychology, 90(6), 1014.

- McElroy, J. C., Hendrickson, A. R., Townsend, A. M., & DeMarie, S. M. (2007). Dispositional factors in internet use: personality versus cognitive style. MIS quarterly, 809-820.

- Pflügner, K., Maier, C., Mattke, J., & Weitzel, T. (2021). Personality profiles that put users at risk of perceiving technostress: A qualitative comparative analysis with the big five personality traits. Business & Information Systems Engineering, 63, 389-402.

- Picazo-Vela, S., Chou, S. Y., Melcher, A. J., & Pearson, J. M. (2010). Why provide an online review? An extended theory of planned behavior and the role of Big-Five personality traits. Computers in human behavior, 26(4), 685-696.

- Rosen, P. A., & Kluemper, D. H. (2008). The impact of the big five personality traits on the acceptance of social networking website. AMCIS 2008 proceedings, 274.

- Sharma, A., & Citurs, A. (2004). Incorporating personality into UTAUT: Individual differences and user acceptance of IT.

- Yang, H. D., Kang, H. R., & Mason, R. M. (2008). An exploratory study on meta skills in software development teams: antecedent cooperation skills and personality for shared mental models. European Journal of Information Systems, 17, 47-61.

References

Costa, P. T., & McCrae, R. R. (1992a). Normal personality assessment in clinical practice: The NEO Personality Inventory. Psychological assessment, 4(1), 5.

Costa Jr, P. T., & McCrae, R. R. (1992b). The five-factor model of personality and its relevance to personality disorders. Journal of personality disorders, 6(4), 343-359.

Contributor(s)

HIBA VP, Indian Institute of Management, Kozhikode, India

Date last updated

23 August, 2023

Please feel free to make modifications to this site. In order to do so, you must register.