Work systems theory

Work system theory

Acronym

WST = work system theory. WSM = work system method, which is based on WST

Alternate name(s)

Work system approach, Work system method, Work system perspective

Main dependent construct(s)/factor(s)

Because this is a systems theory, the idea of dependent and independent variables does not apply directly as it would in a variance theory. The outcomes related to a work system’s operation are perceived or measured in terms of different aspects of the work system’s performance.

Main independent construct(s)/factor(s)

Because this is a systems theory, the idea of dependent and independent variables does not apply directly as it would in a variance theory. The nine elements of the work system framework and the four phases of the work system life cycle model are independent parts of the theory, but should not be viewed as independent or dependent variables, just as a person’s heart and kidneys should not be viewed as independent or dependent variables.

Concise description of theory

The basic idea of WST is that systems in organizations should be viewed as work systems by default. Technologies should be viewed as components of work systems rather than as systems on their own unless there is an intention to analyze a totally automated work system.

Work theory consists of three components: the definition of work system, the work system framework (WSF) and the work system life cycle model (WSLC). The WSF identifies and organizes nine elements of even a rudimentary understanding a work system’s form, function, and environment during a period when it is relatively stable. A work system’s identity remains unchanged during such periods of stability even though incremental changes such as minor personnel substitutions or technology upgrades may occur within what is still considered the same version of the same work system. The WSLC model represents the iterative process by which work systems evolve over time through a combination of planned change (formal projects) and unplanned (emergent) change that occurs through adaptations and workarounds.

Definition: A work system is a system in which human participants and/or machines perform processes and activities using information, technology, and other resources to produce product/services for internal or external customers. Information systems, projects, and supply chains are all special cases of work systems.

· An information system is a work system all of whose processes and activities are devoted to processing information, which occurs through six types of activities, capturing, transmitting, storing, retrieving, manipulating, and displaying information.

· A project is a work system designed to produce a set of product/services and then go out of existence.

· A supply chain is an interorganizational work system devoted to providing materials, other inputs, and conditions required to produce a firm’s products.

· The use of an ecommerce web site can be viewed as a work system in which a customer uses a vendor’s web site to obtain product information and perform purchase transactions.

· Service systems are work systems because they perform processes and activities with the intention of producing benefits for others. Almost all work systems are service systems. The exceptions are work systems whose only beneficiary is the person who performs the work, as in shadow IT systems that individuals operate for their own benefit..

· A totally automated work system such as the operation of a search engine is a work system in which all of the work is done by a machine. The machine (e.g., the search engine) is created by people, but operates autonomously once launched.

The relationship between work systems in general and the special cases implies that the same basic concepts apply to all of the special cases, which also have their own specialized vocabulary. In turn, this implies that much of the body of knowledge for the current information systems discipline can be organized around a work system core, rather than around special cases of IS, such as DSS, CRM, or systematic uses of social media..

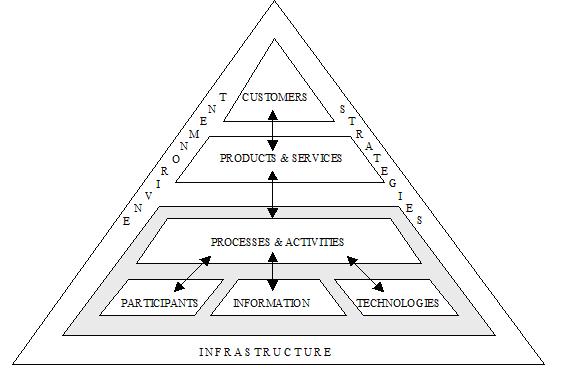

The work system framework (diagram below) was originally developed to help business professionals recognize and understand IT-reliant systems in organizations. It identifies nine elements that are part of even a rudimentary understanding of a work system. Processes and activities, participants, information, and technologies are completely within the work system. Customers and product/services may be partially inside and partially outside because customers often participate in the processes and activities within work systems and because product/services take shape within work systems. Environment, infrastructure, and strategies are largely outside the work system even though they often have direct effects within work systems and therefore are part of a basic understanding of those systems.

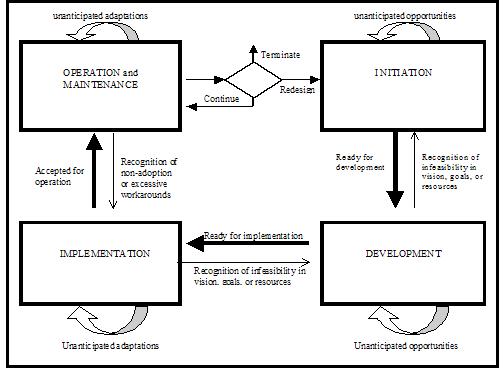

The work system life cycle model (WSLC) represents a dynamic view of how work systems change over time. The WSLC is an iterative model based on the assumption that a work system evolves through a combination of planned and unplanned changes. Planned changes occur through formal projects with initiation, development, and implementation phases. Unplanned changes are ongoing adaptations, workarounds, and experimentation that change aspects of the work system without performing formal projects. The WSLC is fundamentally different from the system development life cycle (SDLC), which is basically a project model rather than a work system life cycle. (Even iterative development models are basically about iterations within a project.) The system in the SDLC is a basically a configuration of hardware and software that is being created. In contrast, the system in the WSLC is a work system that evolves over time through multiple iterations. This evolution occurs through a combination of defined projects and incremental changes resulting from small adaptations, workarounds, and experimentation. The WSLC treats unplanned changes as part of a work system’s natural evolution.

A number of extensions of WST have been developed. These are ideas that build on WST/WSM but go beyond that core of ideas. Extensions of the WST/WSM include:

- a work system metametal that reinterprets and expands upon all of the concepts in the work system framework in order to support more detailed modeling that gets closer to the topics that IT professionals need to resolve in order to produce software.

- a set of work system axioms that are designed to apply to all work systems and therefore to all information systems and work systems.

- a set of normative design principles that apply to most sociotechnical work systems

- a bilateral model call the service value chain framework, which can be used in conjunction with the work system framework when product/services are co-produced by providers and customers.

- a theory of workarounds that describes what happens in the inward looping arrow above the operation and maintenance phase in the WSLC

- a theory of system interactions that describes various types of interactions that may occur between two work systems.

Diagram/schematic of theory

The Work System Framework. (Adapted and slightly updated from Alter, 2006)

The Work System Life Cycle Model (Alter, 2006)

Originating author(s)

Steven Alter

Seminal articles

Sociotechnical researchers have used the term work system for decades (e.g., Trist, 1981; Mumford, 2006). Building on the sociotechnical tradition, Bostrom and Heinen (1977a, 1977b) used the term “work system” extensively in two articles in the first edition of MIS Quarterly. Alter (1999; 2003; 2006) defined the term work system carefully and showed how it could be a central concept for understanding and analyzing IT-reliant systems in organizations. Alter (2013) introduced work system theory (WST), as the theory underlying the work system method (WSM)

Trist, E., (1981). The evolution of socio-technical systems. Occasional paper, 2, p.1981.

Mumford, E. (2006.) “The story of socio‐technical design: Reflections on its successes, failures and potential,” Information Systems Journal, (16:4), pp.317-342.

Bostrom, R. P., and Heinen, J. S., (1977). MIS problems and failures: A socio-technical perspective, MIS Quarterly, Vol. 1, No. 3, pp. 17-32.

Bostrom, R. P. and J. S. Heinen, (1977) “MIS Problems and Failures: A Socio-Technical Perspective. PART II: The Application of Socio-Technical Theory.” MIS Quarterly, 1(4), December, pp. 11-28.

Alter, S. (1999) “A General, Yet Useful Theory of Information Systems,” Communications of the Association for Information Systems, 1(13),

Alter, S. (2003) “18 Reasons Why IT-Reliant Work Systems Should Replace ‘The IT Artifact’ as the Core Subject Matter of the IS Field,” Communications of the Association for Information Systems, 12(23)

Alter, S. (2006) The Work System Method: Connecting People, Processes, and IT for Business Results, Larkspur, CA: Work System Press.

Alter, S. (2008). “Defining Information Systems as Work Systems: Implications for the IS Field.” European Journal of Information Systems,17(5), 448-469.

Alter, S. (2008). “Service system fundamentals: Work system, value chain, and life cycle,” IBM systems journal, 47(1), 71-85

Alter, S. (2013). “Work System Theory: Overview of Core Concepts, Extensions, and Challenges for the Future,” Journal of the Association for Information Systems, 14 (2), 72-121

Originating area

Sociotechnical systems, information systems

Level of analysis

The work system. Organizations consist of multiple work systems.

IS articles that use the theory

(in chronological order). Note: The articles above are not repeated below. Some of the articles below use WST directly. Other articles build on extensions of WST.

Sherer, S. A. and S. Alter (2004) “Information System Risks and Risk Factors: Are They Mostly about Information Systems?” Communications of the Association for Information Systems, 14(2), July, pp. 29-64.

Alter, S. (2004). Desperately seeking systems thinking in the information systems discipline. ICIS 2004 Proceedings, 61.

Petkov, D. and O. Petkova (2006) “The Work System Model as a Tool for Understanding the Problem in an Introductory IS Project,” Proceedings of the 23rd Information Systems Education Conference (ISECON 2006), Dallas, TX, November.

Alter, S. and Wright, R. (2010). Validating Work System Principles for Use in Systems Analysis and Design, Proceedings of ICIS 2010, the 31st International Conference on Information Systems.

Truex, D., Alter, S., and Long, C. (2010). Systems analysis for everyone else: Empowering business professionals through a systems analysis method that fits their needs. European Conference on Information Systems, ECIS 2010.

Truex, D., Lakew, N., Alter, S., and Sarkar, S. (2011). Extending a systems analysis method for business professionals. In European Design Science Symposium (pp. 15-26). Springer Berlin Heidelberg.

Ferrario, R., N. Guarino, C. Janiesch, T. Kiemes, D. Oberle, F. Probst (2011). Towards an ontological foundation of services science: The general service model, in: A. Bernstein, G. Schwabe (Eds.), 10th International Conference on Wirtschaftsinformatik, 16–18 February 2011, Zurich, Switzerland, vol. 2, 2011, pp. 675–684.

Tan, X., Alter, S, and Siau, K. (2011). “Using service responsibility tables to supplement UML in analyzing e-service systems,” Decision Support Systems, 51, 350-360.

Truex, D., Lakew, N., Alter, S., and Sarkar, S. (2011). Extending a systems analysis method for business professionals. In European Design Science Symposium (pp. 15-26). Springer Berlin Heidelberg

Alter, S. (2014). “Theory of Workarounds,” Communications of the Association for Information Systems, 34(55), 1041-1066.

Bock, A., Kaczmarek, M., Overbeek, S. and Heß, M., (2014), November. “A Comparative Analysis of Selected Enterprise Modeling Approaches” PoEM 2014, Practice of Enterprise Modeling, (pp. 148-163).

Niederman, F. and March, S. (2014). “Moving the Work System Theory Forward,” Journal of the Association for Information Systems. 15(6), 346-360

Alter, S. (2015), “Work System Theory as a Platform: Response to a Research Perspective Article by Niederman and March, Journal of the Association for Information Systems, 16(6), 485-515.

Laumer, S., Wirth, J., Maier, C. and Weitzel, T., (2015). A work system theory perspective on user satisfaction: Using multiple case studies to propose a work system success model. DIGIT 2015 Proceedings. 6.

Röder, N., Wiesche, M., Schermann, M., & Krcmar, H. (2015). Workaround Aware Business Process Modeling. In Wirtschaftsinformatik (pp. 482-496).

Alter, S. (2016). “Principles for ‘Purposefully Constructed Activity Systems’ -- A Step toward a Body of Knowledge for Information Systems,” International Conference on Information Systems.

Alter, S., and Bolloju, N. (2016). “A Work System Front End for Object-Oriented Analysis and Design.” International Journal of Information Technologies and Systems Approach (IJITSA), 9(1), 1-18

Koehler, T., and Alter, S. (2016). “Using Enterprise Architecture to Attain Full Benefits from Corporate Big Data while Refurbishing Legacy Work Systems.” Conference on Business Informatics (Industrial Track) (pp. 1-11).

Alter S. (2017) “Answering Key Questions for Service Science,” European Conference on Information Systems, ECIS 2010.

Alter, S. and Recker, J. C. (2017). Using a work system perspective to expand BPM research use cases. Journal of Information Technology Theory and Application, 18(1), 47-71.

Bolloju, N., Alter, S., Gupta, A., Gupta, S., and Jain, S. (2017). Improving Scrum User Stories and Product Backlog Using Work System Snapshots, AMCIS 2017, Americas Conference on Information Systems, Boston, MA. August.

Wong, H. M. L. (2017). “Demystifying and Solving the Knowledge Sharing Problems in a Regional Operations Division of a Global Courier and Delivery Services Firm: An Action Research Approach.”, PhD. Dissertation, City University of Hong Kong.

Mrass, V.; Peters, C. & Leimeister, J. M. (2018): Managing Complex Work Systems via Crowdworking Platforms: The Case of Hamburger Hochbahn and Phantominds. In: Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (HICSS). Waikoloa, HI, USA.

Links from this theory to other theories

Work system theory is related to General systems theory, but focuses specifically on systems within or across organizations.

Work system theory has some resemblance to Soft systems theory, but tries to be more prescriptive about what to consider.

External links

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Work_system , A somewhat outdated Wikipedia article about work systems.

www.stevenalter.com presents basic ideas related to work systems and service systems.

Original Contributor(s)

Steven Alter

Please feel free to make modifications to this site. In order to do so, you must register.

Return to Theories Used in IS Research